Much of my research during the last few years has focused on the eighteenth century botanist and traveller Pehr Löfling, a student of Carl Linnaeus. I am not yet done with him, I think, but last week I submitted the final report on ”Pehr Löfling and the globalization of knowledge, 1729–1756”, a project that ran from 2011 to 2014 and was funded by the Riksbankens Jubileumsfond. Below is the English version of the report’s summary of objectives and outcomes, followed by the list of publications resulting, directly or indirectly, from the project.

Over the next month or two I will reorganise a now defunct Swedish-language research blog on Löfling into a permanent project archive with a variety of documentation and resources. While most of the information will be in Swedish, I plan to include a few pages of overviews on Löfling and the project in English, as well as an extensive list of references and links to related material in Swedish, Spanish and English.

* * *

Objectives and outcomes

The overall objective of this project has been to use the life and travels of Swedish botanist Pehr Löfling (1729–1756), who worked in Spain and South America in the 1750s, to explore and analyse the early wave of knowledge globalisation that Linnaean botany represented. The research has focused on three encounters in the “life geography” of Löfling: between him as a young student and Linnaean taxonomy, between him as a Linnaean “apostle” and the world of Spanish science, and between him as a European (colonial) scientist and indigenous American populations.

In essence, this basic premise has not changed as the project has run its course, although over time I have revised parts of the theoretical framework. In the application I used ideas about centre/periphery and the relationship between concepts like local, national and global to organise the contexts in which Löfling moved. While they were never meant to be applied uncritically, in view of recent discussions within the global history of science about the “circulation of knowledge” and “go-betweens” these notions grew increasingly problematic and have been gradually toned down.

This shift aligns well with my own previous work on the global travels of Linnaeus’s students, where I have challenged what I call Linnaeus’s perspective on these journeys and argued that they should be understood in a broader context where there were many stakeholders with different motives. One of the main results of the project has been an example of this in practice as Löfling, during his time in Spain and South America, did not only try to lay the foundations for a future career by cementing his relationship with Linnaeus and other key figures in Sweden, but also actively worked to make himself known to internationally prominent botanists. Meanwhile, in Madrid he did everything he could to build trust and good relations with Spanish scientists and politicians, on whom he depended for the journey to Cumana and Guayana that might be decisive for his prospects as a naturalist.

The second major finding concerns Löfling’s role in the process by which Linnaean natural history evolved from a national enterprise – albeit one with global roots, as it were – into an endeavour on a European and eventually global scale, often in the service of colonialism. Based on both primary and secondary sources I have been able to significantly deepen our understanding of the implications of a previously known simple fact: that Löfling was one of the first examples of this development. Before any other Linnaean traveller he took part in an actively ongoing colonisation operation, that of the Spanish empire in Cumana province. In the close examination of this aspect of his life and work, I have also been able to engage the discussion about the go-betweens and their role in the global circulation of knowledge, arguing that depending on circumstances European scientists like Löfling could also clearly assume such a role.

The third and last main conclusion also relates to Löfling’s position as a quintessential middleman, situated as he was at the intersection of multiple traditions, cultures and identities in Madrid as well as New Andalusia. Analysing this position by the use of letters written to various types of recipients – family, friends, Linnaeus and other Swedish benefactors, Spanish botanists and officials – I have been able to show how Löfling’s identity was continually being renegotiated based on changing situation(s) and relations. In him, loyalties based on nationality, ethnicity and religious belief were often deeply connected to and entangled with his strong sense of what it meant to be a Linnaean botanist. Thus, qualities that he associated with ‘other’ (and competing) traditions of natural history he also ascribed, to some extent, to the Spanish as a nation; and in his mind this latter category was, in turn, closely associated with the inherent ‘otherness’ of their predominant religion, Roman Catholicism.

In the course of the project new questions have arisen that point to the broader context of Löfling and his work. Firstly, it would be interesting to relate the study of Löfling in more detail to the other stakeholders in his journey and their varying motives, and to explore what this says about the relationship between science, colonialism and politics during the eighteenth century. Such issues have been touched upon within the project, but could be developed significantly based on both primary sources and an extensive literature in Spanish that is rarely cited in Swedish- or even English-language scholarship. Secondly, the work on Löfling has made me more aware of the little-known history of Spanish-Swedish relations from a colonial perspective. A study of the repeated Swedish efforts throughout much of the eighteenth century to acquire a colony from Spain in the Caribbean or on the South American coast could be a very interesting contribution to the globalisation of Swedish history.

Publications

Main publications

1) Kenneth Nyberg, ”Forskare är också människor: Om global historia och forskarbiografiers värde,” in Henrik Alexandersson, Alexander Andreeff & Annika Bünz (eds.), Med hjärta och hjärna: En vänbok till professor Elisabeth Arwill-Nordbladh (Göteborg: Institutionen för historiska studier, Göteborgs universitet, 2014), pp. 65–74; available online at https://kennethnyberg.org/forskare-ar-ocksa-manniskor/ (accessed 23 March 2015).

2) Kenneth Nyberg, ”Från Tolvfors till Orinoco: Pehr Löflings resa och den globala historien,” Historielärarnas förenings årsskrift 2015 (forthcoming, summer 2015), c. 10 pp.

3) Kenneth Nyberg & Manuel Lucena Giraldo, ”Lives of useful curiosity: The global legacy of Pehr Löfling in the long eighteenth century,” in Hanna Hodacs, Kenneth Nyberg & Stéphane Van Damme (eds.), Empire of Nature: A global history of Linnaean science in the long eighteenth century (forthcoming, spring 2016), c. 25 pp.

4) Kenneth Nyberg, ”A world of distinctions: Pehr Löfling and the meaning of difference,” in Magdalena Naum & Fredrik Ekengren (eds.), Encountering the ‘Other’: Ethnic diversity, culture and travel in early modern Sweden (forthcoming, spring 2016), c. 25 pp.

5) Kenneth Nyberg, ”Linnaeus’s apostles and the globalization of knowledge,” in Pat Manning (ed.), Works of Nature (forthcoming, spring 2016), c. 22 pp.

Other project-related publications

6) Kenneth Nyberg, ”Anders Sparrman – konturer av en livshistoria,” in Gunnar Broberg, David Dunér & Roland Moberg (eds.), Anders Sparrman: Linnean, världsresenär, fattigläkare (Uppsala: Svenska Linnésällskapet, 2012), pp. 13–34.

7) Kenneth Nyberg, [review of] ”Torkel Stålmarck, Ostindiefararen Carl Gustav Ekeberg 1716–1784, Acta Regiae Societatis Scientiarum et Litterarum Gothoburgensis, Humaniora 44 (Göteborg: Kungl. Vetenskaps- och Vitterhets-Samhället, 2012). 94 s.,” Sjuttonhundratal 2013, pp. 235–237.

8) Kenneth Nyberg, [review of] ”Gösta Kjellin och Johanna Enckell, Sissi-Jaakko. En klassresa i svenskt 1700-tal (Helsingfors: Schildts 2011). 176 s.,” Historisk tidskrift 2013:1, pp. 93–95.

9) Kenneth Nyberg, ”Anders Sparrman och Stilla havets utforskning,” in Katarina Streiffert Eikeland & Madelaine Miller (eds.), En maritim värld – från stenåldern till idag (Lindome: Bricoleur Press, 2013), pp. 186–192. [Textbook chapter.]

10) Kenneth Nyberg, ”En linneansk forskarkarriär i ett globalt perspektiv: [Review of] Marie-Christine Skuncke, Carl Peter Thunberg – Botanist and Physician: Career-building across the oceans in the eighteenth century (Uppsala: Swedish Collegium for Advanced Study, 2014),” Respons 2014:6, pp. 62–64.

11) Kenneth Nyberg, ”En linneansk karriär [review of Marie-Christine Skuncke, Carl Peter Thunberg – Botanist and Physician: Career-building across the oceans in the eighteenth century (Uppsala: Swedish Collegium for Advanced Study, 2014)],” Svenska Linnésällskapets årsskrift 2014, pp. 161–163.

12) Hanna Hodacs, Kenneth Nyberg & Stéphane Van Damme, ”Introduction,” in Hodacs, Nyberg & Van Damme (eds.), Empire of Nature: A global history of Linnaean science in the long eighteenth century (forthcoming, spring 2016), c. 30 pp.

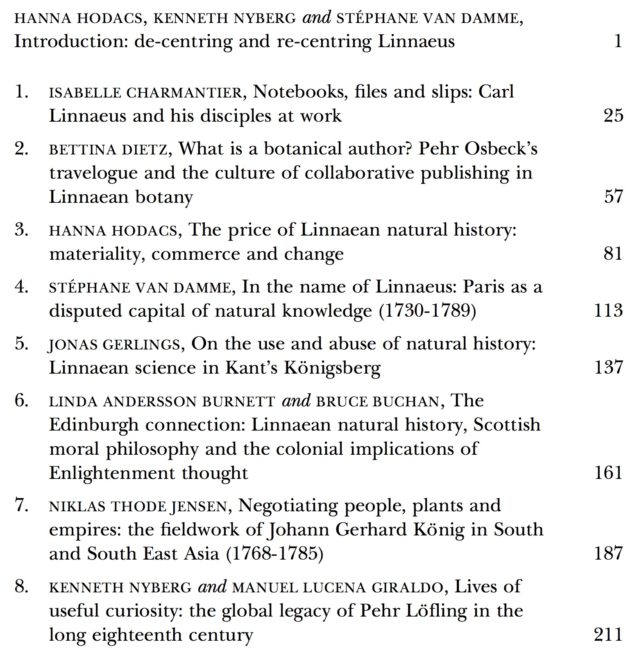

Although six months late, here is a brief post to introduce a new(ish) book I am both excited and proud to be a part of: Hanna Hodacs, Kenneth Nyberg and Stéphane Van Damme (eds.), Linnaeus, natural history and the circulation of knowledge, Oxford University Studies in the Enlightenment 2018:1 (Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 2018). Published last January, this volume – with contributions by ten scholars from almost as many countries – examines the circulation of knowledge about nature in the long eighteenth century. As the back cover puts it, in the book we ”argue for the need to re-centre Linnaean science and de-centre Linnaeus the man by exploring the ideas, practices and people connected to his taxonomic innovations”. (See below for the table of contents.) Apparently this is just what many people had been waiting for, because a few days ago I and my co-editors received word that the volume has already sold out of its (admittedly modest) first print run with a second printing now underway.

Although six months late, here is a brief post to introduce a new(ish) book I am both excited and proud to be a part of: Hanna Hodacs, Kenneth Nyberg and Stéphane Van Damme (eds.), Linnaeus, natural history and the circulation of knowledge, Oxford University Studies in the Enlightenment 2018:1 (Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 2018). Published last January, this volume – with contributions by ten scholars from almost as many countries – examines the circulation of knowledge about nature in the long eighteenth century. As the back cover puts it, in the book we ”argue for the need to re-centre Linnaean science and de-centre Linnaeus the man by exploring the ideas, practices and people connected to his taxonomic innovations”. (See below for the table of contents.) Apparently this is just what many people had been waiting for, because a few days ago I and my co-editors received word that the volume has already sold out of its (admittedly modest) first print run with a second printing now underway.